In life, she was the queen of Tejano music. In death, the 23-year-old singer is becoming a legend

By RICK MITCHELL

Copyright 1995 Houston Chronicle

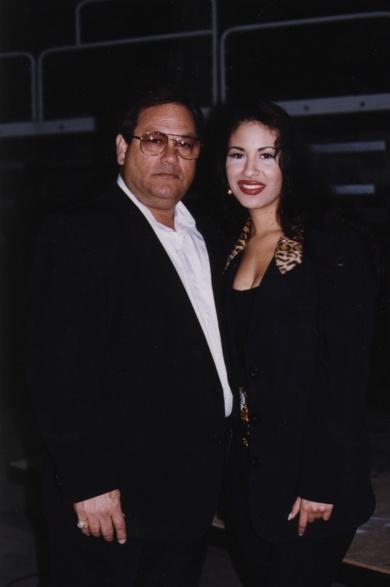

Abraham Quintanilla tried to remember his daughter as she'd looked

the last time he saw her, just the day before. Selena

Quintanilla-Perez was a full-grown woman of 23, a budding superstar

who dreamed of raising a big family with her guitarist/husband once

her music career settled down. She had a smile that could torch up

the night, and a figure that turned heads wherever she went. But the

only image that would come into focus in Abraham's mind was that of

an 8-year-old girl, standing nervously behind the microphone at the

family restaurant in Lake Jackson. Even back then, Abraham had been

convinced that Selena was destined to become a star. A former

musician himself, he recognized the rare power and precise pitch in

her voice.

Abraham Quintanilla tried to remember his daughter as she'd looked

the last time he saw her, just the day before. Selena

Quintanilla-Perez was a full-grown woman of 23, a budding superstar

who dreamed of raising a big family with her guitarist/husband once

her music career settled down. She had a smile that could torch up

the night, and a figure that turned heads wherever she went. But the

only image that would come into focus in Abraham's mind was that of

an 8-year-old girl, standing nervously behind the microphone at the

family restaurant in Lake Jackson. Even back then, Abraham had been

convinced that Selena was destined to become a star. A former

musician himself, he recognized the rare power and precise pitch in

her voice.

He had staked everything on her talent. From the band's early years

travelling the South Texas back roads in an old, beat-up van with a

foldout bed in the back, to playing for 60,000 rodeo fans in the

Astrodome, Selena had become the biggest star in Tejano music. She

was a household name in Mexico and much of Latin America and was on

the verge of an unprecedented breakthrough to the English-speaking

pop audience. Now, through a tragic turn of events, the dream

Abraham had shared with his wife, Marcela, and their three children

had been shattered. That morning, Selena had failed to show up at Q

Productions studio. It wasn't unusual for her to be late. Perpetual

tardiness was part of her charm.

But on this particular Friday morning, it was surprising that Selena

hadn't at least called. She had a 10 a.m. appointment with her older

brother, A.B., and sister, Suzette, to cut the vocal tracks for a

demo tape of a new song A.B. had written. Selena also was midway

through the recording of her first crossover album, with lyrics in

English. The album was coming together slowly because of her hectic

schedule. Eleven a.m. came and went, but there was still no word

from Selena. A.B. phoned Christopher Perez, her husband, who said

she'd left the house that morning at 9, while he was still in bed.

Chris didn't know where she'd gone, but he guessed that it had

something to do with Yolanda Saldivar, the former president of

Selena's fan club. Abraham and A.B. went to lunch. They returned to

the office just as the phone rang. Abraham's sister-in-law screamed

that Selena had been in an accident. Her father raced to the

hospital emergency room at Memorial Medical Center.

returned to

the office just as the phone rang. Abraham's sister-in-law screamed

that Selena had been in an accident. Her father raced to the

hospital emergency room at Memorial Medical Center.

At the hospital, Abraham learned there had been no accident. Selena

had been shot in the back and was listed as dead on arrival, a

doctor said, but they'd managed to get her heart started again

briefly and had given her a blood transfusion. Abraham, who'd

followed his father into the Jehovah's Witnesses faith some years

earlier, immediately reacted to the transfusion. "No! She doesn't

want that," he yelled. Only then did the horrible finality of the

doctor's words begin to sink in. Selena was dead. To children

growing up in barrios such as La Molina, the working-class Corpus

Christi neighborhood where the Quintanillas lived, Selena was la

reina del pueblo, a successful entertainer who'd never lost touch

with her roots. But to Abraham, she was still his little girl. The

one who had bounced up and down on his bed where he lay playing his

old guitar and singing the Mexican standards and pop songs he loved.

The beautiful little girl was gone.

The Quintanilla family was not alone in its grief. As word of

Selena's violent death on March 31 spread north and south out of

Corpus Christi, fans reacted first with disbelief, then with a

massive, public display of adoration. Signs appeared in cars

declaring "We love you, Selena!" or "Con tanto amor!" Churches

hastily organized prayer vigils. Tejano radio stations played

Selena's music around the clock. Record stores sold out of her

albums. On the weekend following her death, thousands of mourners

from Texas, Mexico and points farther made the pilgrimage to Corpus

Christi to pay their last respects. That Sunday, they filed into the

Corpus Christi Convention Center, where Selena's body lay in a black

coffin surrounded by white roses. After a rumor circulated that the

casket was empty, the family agreed to open it to confirm that the

horrible news was true. The Days Inn motel where Selena was shot

became a shrine to her memory, with messages from fans scrawled on

the walls of the room where the singer had met with her accused

killer, Saldivar, just before her death. Saldivar was suspected of

embezzling money from Selena's fan club. Selena had gone to the

hotel alone, at Saldivar's request, hoping to obtain documentation

that the accusations were untrue. Flowers and cards covered the

fence surrounding the house where Selena and Chris lived. Votive

candles lined the driveway.

Outside the clothing boutiques Selena operated in Corpus and San

Antonio, hawkers sold souvenir T-shirts and ball caps bearing her

image. Following Selena's burial in a private ceremony on April 3,

her Seaside Memorial Park gravesite also became a shrine. Every

evening, the cemetery had to cart away truckloads of cards and

flowers. Abraham expressed surprise and gratitude at the outpouring

that followed his daughter's death. He speculated that Selena's

appeal went deeper than the music. "I knew that a lot of people

cared for Selena," he said. "I could see it in their faces

everywhere we played. But I'm really surprised by the magnitude of

this thing. I think people are tired of the wickedness of this

system. She was a good person, a clean person with morals. They

could see that. And there's not too much of that left in this

world." The week after Selena was killed, People magazine put her on

the cover in Texas and other Southwestern states. When the issue

instantly sold out at newsstands, the magazine decided to do a

commemorative issue in Selena's honor -- only the third such tribute

in the publication's history.

Outside the clothing boutiques Selena operated in Corpus and San

Antonio, hawkers sold souvenir T-shirts and ball caps bearing her

image. Following Selena's burial in a private ceremony on April 3,

her Seaside Memorial Park gravesite also became a shrine. Every

evening, the cemetery had to cart away truckloads of cards and

flowers. Abraham expressed surprise and gratitude at the outpouring

that followed his daughter's death. He speculated that Selena's

appeal went deeper than the music. "I knew that a lot of people

cared for Selena," he said. "I could see it in their faces

everywhere we played. But I'm really surprised by the magnitude of

this thing. I think people are tired of the wickedness of this

system. She was a good person, a clean person with morals. They

could see that. And there's not too much of that left in this

world." The week after Selena was killed, People magazine put her on

the cover in Texas and other Southwestern states. When the issue

instantly sold out at newsstands, the magazine decided to do a

commemorative issue in Selena's honor -- only the third such tribute

in the publication's history.

Yet, even as Selena's Spanish albums topped the Latin charts and

entered the mainstream pop charts in the weeks after her death, many

were still wondering how the Texas singer could have gained such a

large and devoted following. While shock jock Howard Stern joked

about the tragedy, others simply asked, "Who's Selena?" Selena was

Tejano music's brightest hope for the future. Had she lived, she

might well have been the first international superstar to come out

of the Tejano market. A vivacious entertainer who could sing any

style of music, her potential was unlimited. Even after her death,

Selena could become the first Tejano artist to break through to the

mainstream pop market. In July, EMI Records will release an album

including five English tracks, plus remixed and re-recorded versions

of her biggest Spanish hits. "We're going to do our best to give her

that English hit she wanted so badly," says EMI vice president Nancy

Brennan. The third child of Abraham and Marcela Quintanilla, Selena

was born on April 16, 1971, at the Community Hospital of Brazosport.

The family lived in nearby Lake Jackson, where Abraham was employed

by Dow Chemical Co. as a shipping clerk.

To Abraham, it seemed as if Selena was born happy. "She was just

full of life," he says. "She was always joking and clowning around."

To their neighbors in Lake Jackson, 55 miles south of Houston, the

Quintanillas looked like a loving, patriarchal family. "They were a

very close-knit family," says Carmen Read, who lived with her

husband, Ed, and their two sons around the corner from the

Quintanillas' house on Caladium Street. "I probably fussed at every

other kid in the neighborhood, but I don't think I ever fussed at

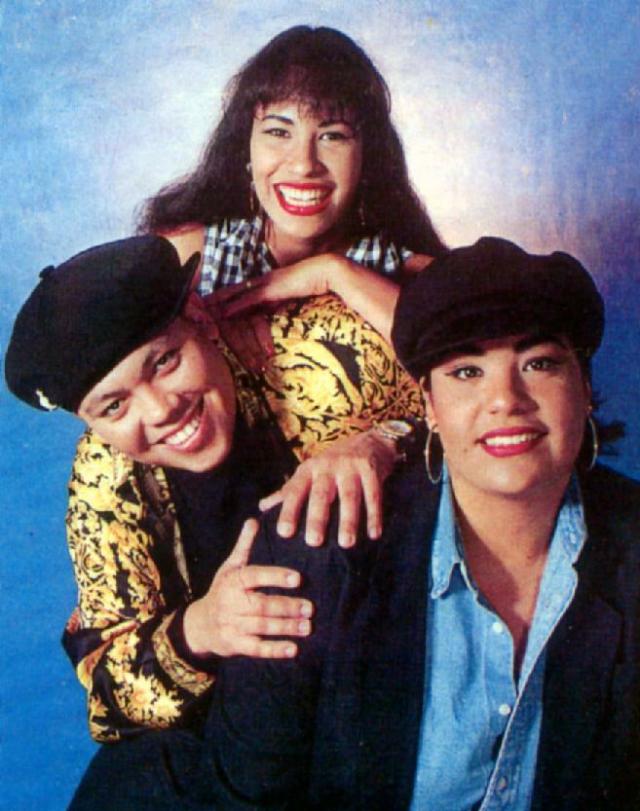

those kids. They were so well-behaved." A.B. (short for Abraham

Quintanilla III) was eight years older than Selena; Suzette was four

years older. But if either ever resented their little sister tagging

along, it didn't show. "They were so close," says A.B.'s childhood

friend David Read. "I never recalled them arguing or not getting

along when they were out playing. They never had a complaint about

anything." Carmen took special notice of the Quintanillas because

they were one of the few Hispanic families in Lake Jackson at the

time. They reminded her of her own childhood: She grew up in one of

the only Mexican-American families in Silsbee, in East Texas.

(short for Abraham

Quintanilla III) was eight years older than Selena; Suzette was four

years older. But if either ever resented their little sister tagging

along, it didn't show. "They were so close," says A.B.'s childhood

friend David Read. "I never recalled them arguing or not getting

along when they were out playing. They never had a complaint about

anything." Carmen took special notice of the Quintanillas because

they were one of the few Hispanic families in Lake Jackson at the

time. They reminded her of her own childhood: She grew up in one of

the only Mexican-American families in Silsbee, in East Texas.

I always felt that (Abraham) was maybe a little too hard on the

kids," she says. "He was a typical hard-working, strict Mexican

father. He definitely was the head of the household. I was raised in

that same kind of household. Maybe that's why I always paid more

attention to them. But I think those that lived here knew that they

weren't a common, everyday family." Abraham acknowledges that he was

a strict father. He didn't allow his children to sleep over at other

kids' houses, and he didn't believe in casual dating. If he was too

hard on his kids, he says, it's because he remembered his own wild

childhood in Corpus Christi. "All these years, I knew where my kids

were 24 hours a day," he says. "Maybe I overdid it, I don't know. I

just didn't want them to go through what I went through. I was a

street kid. My parents couldn't control me when I was young." Early

on, Selena began to exhibit an irrepressible personality all her

own. Nina McGlashan, Selena's first-grade teacher at O.M. Roberts

Elementary School, remembers her as a delightful child.

"She had a very bubbly, positive-type of personality," says the

former Nina Smith. "She was eager to please and eager to learn. The

type of little kid that you would like to have in a class. I

remember, too, that she had a little shyness about her." All three

Quintanilla children showed an early interest in music, their father

says. They came by it naturally. In the 1950s and '60s, prior to

moving to Lake Jackson, Abraham led a band in Corpus Christi called

Los Dinos. The name was taken from the Italian slang word for los

muchachos, the boys. Los Dinos played a mix of early rock 'n' roll

and traditional Mexican music, with three-part harmony vocals and a

horn section. But in those days, opportunities were limited in what

was known as Tex-Mex or Chicano music. Abraham eventually gave up on

the music business and took a job at Dow to support his growing

family. Selena was 6 when Abraham noticed that she had a remarkable

voice. He was teaching A.B. a few chords on the guitar when Selena

burst into song. "I always wanted to go back into the music

business, but I felt like I was already getting too old, and my kids

were growing up," Abraham says. "When I found out Selena could sing,

that's when the wheels started turning in my mind. I saw the chance

to get back in the music world through my kids."

While many parents have entertained similar fantasies, Abraham was

convinced that he had a special talent to work with. "I felt that

Selena had it since she was a little girl," he says. "She had that

extra thing that makes an artist. Of course, nobody believed me at

that time." With his wife's support, Abraham converted his garage

into a music studio. A friend gave him an old Sears Silvertone bass,

and he bought a set of drums. A.B. picked up the bass, and Suzette

was assigned to the drums. "They knew zero about music," Abraham

says. "I just placed the instruments in their hands and said, 'All

right, let's go.' "At first, they were too young," he says. "They

had a short attention span. They would want to go play with the

other kids. Then they started getting into the music. They started

creating. You know how it is." The little family band rehearsed

almost every day after school. "We did all the normal kid things

together," says David Read. "But they always knew when it was time

to go practice. I used to go in there and watch sometimes. Selena

always seemed to be having a great time."

While many parents have entertained similar fantasies, Abraham was

convinced that he had a special talent to work with. "I felt that

Selena had it since she was a little girl," he says. "She had that

extra thing that makes an artist. Of course, nobody believed me at

that time." With his wife's support, Abraham converted his garage

into a music studio. A friend gave him an old Sears Silvertone bass,

and he bought a set of drums. A.B. picked up the bass, and Suzette

was assigned to the drums. "They knew zero about music," Abraham

says. "I just placed the instruments in their hands and said, 'All

right, let's go.' "At first, they were too young," he says. "They

had a short attention span. They would want to go play with the

other kids. Then they started getting into the music. They started

creating. You know how it is." The little family band rehearsed

almost every day after school. "We did all the normal kid things

together," says David Read. "But they always knew when it was time

to go practice. I used to go in there and watch sometimes. Selena

always seemed to be having a great time."

It wasn't long before Abraham left Dow to open a Mexican food

restaurant, Papagayo, in Lake Jackson. He made sure it had a stage

and a dance floor. Selena and the band performed on weekends and

developed a local following. "It was so unusual," says Ed Read. "You

wouldn't expect to see a kid get up and sing in a restaurant like

that. Her voice was a little higher, but she was on key and she

always had a lot of enthusiasm." Abraham keeps a tape of 9-year-old

Selena singing a Spanish version of Rick James' funk classic "Super

Freak." While her voice is a bit squeaky, the phrasing is on the

money. "I can see her in my mind," Abraham says. "She was an awesome

dancer as a little girl. She had a lot of what black people would

call soul. And she could sing any kind of music." Nineteen-year-old

Rena Dearman answered an ad Abraham put in the Brazosport Facts for

a lead guitarist and a keyboardist. Her boyfriend (later husband)

Rodney Pyeatt played guitar; she played keyboards.

Dearman says she was impressed the first time she heard Selena sing.

"I didn't expect to hear what I heard," she says. "Of course, her

intonation was going to be higher. But it's what she did with the

notes. This girl had some vibrato on her. She could make it work.

Her release from the notes, it wasn't like your everyday little girl

singing. She sounded more like a young woman." Abraham pushed the

band hard to improve, Dearman says. Every day they weren't playing

at the restaurant, they were in the garage practising. The

repertoire was mostly Top 40 hits sung in English and the occasional

pop oldie with Spanish lyrics that Abraham had translated. Then he

started writing his own songs in Spanish for the band. Dearman came

to feel like a member of the family, and she looked up to Abraham.

He had a temper, but he was fair. "I respected what he was trying to

accomplish. When he would be the way he is, I didn't take it the

wrong way. He was taking care of business. The man had a goal. He

knew what he was doing. And he was a good daddy. He loved those

kids."

As it turned out, Abraham was better at managing a band than he was

at running a restaurant. "I was inexperienced in the restaurant

business," he says. "One day I decided that's what I wanted to do.

The following week I'm already leasing the place. I had a big

overhead. All the money I had saved went into the initial cost of

opening." And when the oil business dried up in the early '80s, the

restaurant went broke. Abraham had to borrow money from his brother

Hector to move his family back to his hometown of Corpus. The band

became the household's sole means of support. It might have seemed

like a desperate situation. But Abraham says he didn't see it that

way. "I always knew that Selena was gonna go. I never had any

doubt." The band traveled all over the state, from Lake Jackson to

Laredo to El Paso, playing little clubs, wedding dances and

quinceaneras. There were seven people in the old van. Abraham was

the manager and sound engineer, and Marcela served as light

technician. Selena enrolled in junior high school in Corpus. But the

band's schedule often forced her to miss Friday and Monday classes.

After a few months, she dropped out and continued her education

through correspondence courses. She earned a GED at 17.

inexperienced in the restaurant

business," he says. "One day I decided that's what I wanted to do.

The following week I'm already leasing the place. I had a big

overhead. All the money I had saved went into the initial cost of

opening." And when the oil business dried up in the early '80s, the

restaurant went broke. Abraham had to borrow money from his brother

Hector to move his family back to his hometown of Corpus. The band

became the household's sole means of support. It might have seemed

like a desperate situation. But Abraham says he didn't see it that

way. "I always knew that Selena was gonna go. I never had any

doubt." The band traveled all over the state, from Lake Jackson to

Laredo to El Paso, playing little clubs, wedding dances and

quinceaneras. There were seven people in the old van. Abraham was

the manager and sound engineer, and Marcela served as light

technician. Selena enrolled in junior high school in Corpus. But the

band's schedule often forced her to miss Friday and Monday classes.

After a few months, she dropped out and continued her education

through correspondence courses. She earned a GED at 17.

Not everyone approved of the family's unusual lifestyle. Abraham

says his father and brother told him, "You're going to ruin your

kids. They'll be surrounded by drinking and drugs. It's going to

have an effect on them." But Selena did not seem at all upset about

missing out on a normal adolescence, Dearman says. "The only thing I

knew is that she loved what she was doing. She was having fun. I

don't think she'd have been as happy doing something else if she

wasn't singing. When she was onstage, she was into doing her thing.

If the people responded, so much the better."

While Selena was the star of the show, she remained unaffected by

the attention she received onstage. "She never got haughty with us.

She never changed," Dearman says. "She was as fun-loving back then

as she would be later." Dearman's most vivid memories from the early

years of the band are the long conversations she shared with the

family members in the back of the van. While Pyeatt and Abraham

sometimes engaged in intense religious discussions -- Pyeatt was a

Baptist, Abraham a Jehovah's Witness -- the kids talked about more

personal things.

"I know how they got to be the way they are," Dearman says. "It's

because of their parents. Selena grew up to be a good girl. They

were taught work ethics, compassion and how not to snub people. They

believed that if you treat people good, it'll come back to you in

the end." Dearman left Selena's band when Pyeatt decided to form his

own country band. She really didn't want to quit, but she felt she

had to follow her husband. The pair divorced several years later. "I

was willing to back up Selena for as long as it took," she says. "I

had so much confidence in Abraham. He was going to make the world

see what he saw in Selena. I know A.B. felt the same way. They knew

they had something special there." But for all his pride and

conviction, Abraham admits he had an eye-opening experience when he

booked the band to open for Mazz at the fairgrounds in Angleton. It

was 1983. Mazz was the hottest thing in the Tejano market at the

time.

"When we got to the hall, their road crew had already set up,"

Abraham says. "When I saw all their equipment, I freaked out. When I

was playing, this kind of equipment didn't exist, like crossovers

and equalizers. On one side, they had a stack of about 30 speakers

and 30 more speakers on the other side. "I told my son A.B, `You

know what? I think we're at the wrong place. I think this is a rock

'n' roll dance or something.' "We started walking out, and the

promoter came in. I said, `Is this the place where we're gonna play

tonight?' He said, `Yes.' I said, `Whose equipment is that?' He

said, `Mazz.' "That night, after Selena opened up the show for them,

they came on. It totally scared me. That kick-drum was so powerful

it shook my shirt, and I had never seen smoke and lights like that.

"When we got to the hall, their road crew had already set up,"

Abraham says. "When I saw all their equipment, I freaked out. When I

was playing, this kind of equipment didn't exist, like crossovers

and equalizers. On one side, they had a stack of about 30 speakers

and 30 more speakers on the other side. "I told my son A.B, `You

know what? I think we're at the wrong place. I think this is a rock

'n' roll dance or something.' "We started walking out, and the

promoter came in. I said, `Is this the place where we're gonna play

tonight?' He said, `Yes.' I said, `Whose equipment is that?' He

said, `Mazz.' "That night, after Selena opened up the show for them,

they came on. It totally scared me. That kick-drum was so powerful

it shook my shirt, and I had never seen smoke and lights like that.

"On the second set, I didn't want my kids to go back on. I was

embarrassed. We had a little rinky-dink sound system. I found out

that night that things had changed from the last time I'd been in

the music business."

Selena made her commercial recording debut with Los Dinos when she

was 12. Her first full album, "Mis Primeras Grabaciones," was

released in 1984 on Corpus Christi's Freddie label, one of the

oldest and most established independent Tex-Mex outfits. Rick

Longoria, who engineered the session for label owner and producer

Freddie Martinez, recalls that Selena cut the vocals in just a few

takes. "She was very professional," Longoria says. "She'd be sitting

there while the session was going on, doing little girl things. It

was kind of hard to believe that she was the vocalist. "But when she

started to sing, it was no problem. I've done sessions with people

twice her age where we'd be there doing things over and over because

they couldn't get it right." A single from the album, Ya Se Va,

generated some airplay, but the album didn't sell well. Selena y Los

Dinos promptly left Freddie for the Cara label, then moved on to the

Manny label. "Right from the start, we thought she had some good

talent," says Longoria, who now handles marketing and promotion for

Freddie. "But she still needed to develop. We thought it would take

about three or four years before she came into her own, and that's

exactly what happened.

While Selena emerged as a recording artist, A.B. developed as a

songwriter and producer. He was motivated by the need to provide

Selena with strong, original material. "We had no songs. We were

constantly looking for material," Abraham says. "A.B. would approach

Luis Silva, who was a strong writer in the market, and he would

ignore us. A.B. got upset. I said, 'Son, you need to go in that room

there and just break your head until you write something good.'

"That was the beginning." One of A.B.'s first efforts, "Dame un

Beso," was a moderate hit. A.B., who was already the band's arranger

and producer, soon took over as Selena's chief songwriter. Band

member Ricky Vela also wrote, sometimes in collaboration with A.B.

Although Selena could sing in any style, the band's versatile

approach was dictated as much by necessity as by choice.

"In certain areas of Texas, the Valley, for example, accordion music

is very strong," says Abraham. "When we would go to the Valley, we

would do more accordion-type songs, using the keyboard. "In parts of

West Texas, they want the cumbias, so we would give them more

cumbias. And in Houston and Dallas, the young people want more pop

music, so that's what we'd do." Daniel Bustamente, producer of

Houston's Festival Chicano, remembers Selena's first appearance at

Miller Outdoor Theater, when she was just 15. "She was nervous," he

says. "She was playing second to Ram (Herrera) or Little Joe. The

music was still not as full, but she always impressed everybody with

that voice. The way she was able to do different things with her

voice was like an opera singer, in a sense." By 1988, Selena was

popular enough in the Texas market that she was voted female

vocalist of the year at the Tejano Music Awards in San Antonio. She

would go on to win the award for seven consecutive years. Selena's

albums for the Manny label were selling in the range of

20,000-25,000 copies, a respectable figure for a regional Tejano

artist. She also was gradually building a reputation beyond the

Texas borders.

But the Quintanillas were hardly getting rich. Johnny Canales, the

Corpus Christi-based radio and television personality, recalls a

trip he took to Idaho on the Los Dinos bus. "They were living on

beanies and wienies," Canales says. "She lived through those hard

times. That's why, for her, the good times were nothing. She never

changed." On the front of the band's bus, above the windshield where

touring acts customarily put their names, was the pointed disclaimer

"Nobody You Know." It's still there. The turning point in Selena's

career came in 1989. Jose Behar, the former head of Sony's Latin

music division, had just launched the EMI Latin label. He'd come to

the Tejano Music Awards looking for new acts to sign. Selena was his

first discovery. "I was with a friend of mine, Mario Ruiz, who's now

the president of EMI Mexico," Behar says. "We were standing at the

back of the auditorium when we saw her. Mario and I looked at each

other like, `Wow. This is special.'

Dinos bus. "They were living on

beanies and wienies," Canales says. "She lived through those hard

times. That's why, for her, the good times were nothing. She never

changed." On the front of the band's bus, above the windshield where

touring acts customarily put their names, was the pointed disclaimer

"Nobody You Know." It's still there. The turning point in Selena's

career came in 1989. Jose Behar, the former head of Sony's Latin

music division, had just launched the EMI Latin label. He'd come to

the Tejano Music Awards looking for new acts to sign. Selena was his

first discovery. "I was with a friend of mine, Mario Ruiz, who's now

the president of EMI Mexico," Behar says. "We were standing at the

back of the auditorium when we saw her. Mario and I looked at each

other like, `Wow. This is special.'

"But I turned to him and I said, `It's interesting. Women don't sell

in the Tejano market.' And they really hadn't. Yet I said to myself,

`This is the crossover act I'm looking for.' "So I went backstage to

meet her and she said, `Y'all from EMI? Yeah, right.' And she kept

talking to some other people. I said, `Excuse me, I'm really from

EMI.' And she said, `Yeah, right' again. I think she thought I was

some jerky fan or something, I don't know. "I ended up talking to

her dad. The real reason I signed Selena, and her family knows this,

was not to sell a lot of records in the Latin Tejano market. The

God's honest truth is I never thought she'd sell a half-million

units in Spanish. It just wasn't on the agenda. "The reason I signed

her is because I thought I had the next Gloria Estefan." Selena's

first couple of albums for EMI sold only marginally better than her

Manny releases. Her breakthrough hit was "Buenos Amigos," a 1991

duet with Alvaro Torres. Thanks in part to a sophisticated video

that featured Selena and Torres crooning in front of a string

orchestra, the ballad went to No. 1 on the Billboard Latin tracks

chart and introduced Selena to audiences on the East and West

coasts.

She followed this with a guest appearance on "Dondequiera Que Estés"

by the Barrio Boyzz, Latin music's answer to New Kids on the Block

and Boyz II Men. Selena was seen in the video singing and dancing in

hip-hop formation with the Boyzz against an urban backdrop. Clearly,

there was more to this Tejana than accordions and cowboy hats. These

videos opened the door for Selena to enter the international Latin

market with her own hits, "La Carcacha" and "Como la Flor." While

Tejano artists Mazz and La Mafia had toured in Mexico, Selena was

the first to truly conquer the huge audience south of the border.

"For the first time, we exposed Mexicans to what Tejano music was,"

says Behar. "And once you go into Mexico, that tidal wave is felt in

California." Canales, whose Corpus Christi TV program is syndicated

internationally, agrees that Mexico was the key. "As soon as she hit

Mexico, we knew she was gone," he says. "For a Tejano artist to

cross into that market is hard. She took it over like it was

nothing."

Selena's success in Mexico and other Latin American countries was

aided by A.B.'s ability to craft a tropical, international sound.

Where Tejano music's deepest roots are in the bouncy

norteño/conjunto polka rhythms popular in Northern Mexico and Texas,

Selena y Los Dinos invited listeners to "Baila Esta Cumbia." An

Afro-Caribbean cousin to salsa and merengue, cumbia originated in

Colombia. As it migrated north through Central America and Mexico,

the music adapted to each region. In Colombia, it's often played in

a big-band style, like salsa. In Texas, accordion-based conjuntos

play stripped-down cumbias along with the polkas and two-steps.

A.B.'s approach with Selena was more ambitious. On "Techno Cumbia,"

from the 1994 album "Amor Prohibido," he added elements of funk,

reggae and salsa into a high-tech dance mix. "I've studied it, and I

found a way to do it," A.B. said in an interview three weeks before

Selena's death. "The cumbia can get airplay in Puerto Rico, New

York, Miami, Mexico, anywhere."

It is A.B.'s contention that Tejano music's core market has not

grown all that much in the last 10 years. What has changed is the

ability of certain Tejano artists to appeal to the wider Latin pop

audience. "They call us Tejano, and yes, we are from Texas. But a

lot of the music we're playing is from Mexico and South America," he

said. Selena y Los Dinos' music is "a mixture of tropical, reggae,

cumbia, all these things. It's got pop influences to it, too." A.B.,

who produced Selena's Spanish albums, was also co-producing three

tracks on her English debut. While he acknowledged the record

label's reasons for bringing in outside producers, he felt he had an

advantage over other songwriters and producers working with his

sister. "I've been with Selena since she was 6 years old," he said.

"I've backed her every night on bass. I've seen the reaction, and

felt the vibe. It's a piece of cake."

It is A.B.'s contention that Tejano music's core market has not

grown all that much in the last 10 years. What has changed is the

ability of certain Tejano artists to appeal to the wider Latin pop

audience. "They call us Tejano, and yes, we are from Texas. But a

lot of the music we're playing is from Mexico and South America," he

said. Selena y Los Dinos' music is "a mixture of tropical, reggae,

cumbia, all these things. It's got pop influences to it, too." A.B.,

who produced Selena's Spanish albums, was also co-producing three

tracks on her English debut. While he acknowledged the record

label's reasons for bringing in outside producers, he felt he had an

advantage over other songwriters and producers working with his

sister. "I've been with Selena since she was 6 years old," he said.

"I've backed her every night on bass. I've seen the reaction, and

felt the vibe. It's a piece of cake."

"Amor Prohibido" spawned four No. 1 Latin singles, including the

title track, "No Me Queda Más," "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" and "Fotos y

Recuerdos." The last tune is an inspired Spanish cover of Chrissie

Hynde and the Pretenders' '80s rock classic, "Back on the Chain

Gang." The album knocked Gloria Estefan's "Mi Tierra" out of the top

spot on the Latin chart and has sold more than 800,000 copies

worldwide. It is destined to pass 1 million this year. Yet A.B. says

he accomplished only half of what he set out to do on "Amor

Prohibido." His vision of a Pan-American, tropical-pop blend

incorporating all his influences remains unfulfilled. Selena's

success south of the border was not without complications. Although

she sang in Spanish, she grew up speaking English. In the early days

of the band, Abraham had to teach her the Spanish lyrics

phonetically. She was unable to do interviews with the Mexican media

without an interpreter. "My first language is Spanish, hers is

English," says Manolo Gonzalez, the Cuban-born vice president in

charge of EMI's San Antonio office. "When she talked to me, she

talked to me in English, never in Spanish.

"But you see, Selena was a smart girl. She had the intuition to know

what people wanted to see and hear. In the last four years, she made

it a point to learn (Spanish). When we went to Mexico in the last

month of 1994, I couldn't believe how well she could handle the

press." Selena's longtime fans had watched her mature into a

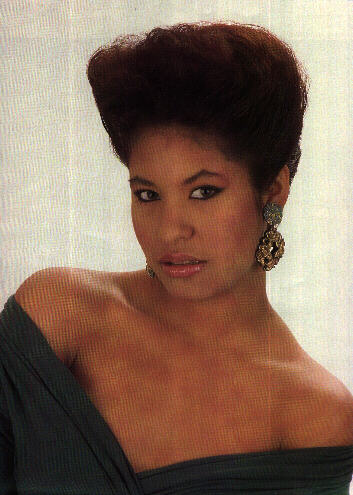

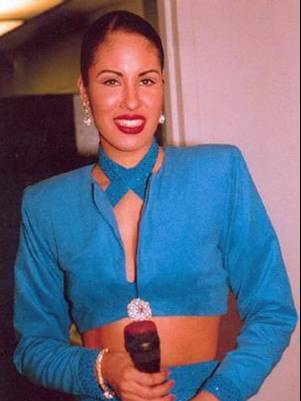

stunning young woman. She often performed in skin-tight pants and

low-cut bustiers that led some to label her "the Mexican Madonna."

But despite the comparisons, Selena wouldn't compromise her morals

to further her career. She could be sexy onstage, but she was never

vulgar. She once turned down a role in a Mexican soap opera because

there was a scene that called for a steamy kiss. "I wouldn't be

comfortable with that; she wouldn't be comfortable with that,"

Abraham said at the time. "Selena has an appeal with young kids, 5

to 10 years old, as well as older folks, you know."

Jose Behar says the record label never told Selena what to sing or

how to look, although he did dictate that she appear on her album

covers alone, rather than with the band. "The only thing she and

Madonna had in common was bustiers," Behar says. "Selena never

stooped to those levels. Great artists don't have to do that." He

compares Selena to a cross between Whitney Houston and Janet Jackson

in terms of her image and vocal range. Canales goes a step further.

"I'd say she's like those people, but better," he says. "Those

people never sang Tejano. She could do what they do, but it would be

hard for them to do what she does." Still, it took the better part

of four years before Behar finally was able to convince EMI's pop

division that he had a potential crossover superstar on his roster.

It seemed that no sooner would he have the right executive persuaded

than that person would leave the company and he'd have to start all

over again. "All he ever talked about was Selena," remembers Nancy

Brennan, EMI's vice president of artist and repertoire. "He was like

a broken record, `Selena, Selena . . . ' "

Brennan's first exposure to Selena was at the Billboard Latin Music

convention in Las Vegas two years ago. Brennan was there to see Jon Secada, an EMI artist who was enjoying huge success in the English

and Spanish markets simultaneously. Selena happened to be opening

the show. Brennan was suitably impressed. Selena was signed by EMI's

SBK subsidiary in December 1993. But it was another year before she

could begin work on her debut album in English. First there was the

touchy matter of selecting the right material and producers. Then

"Amor Prohibido," somewhat unexpectedly, became a huge hit in the

Latin market. Between touring with the band, filming commercials and

movie roles, and overseeing the opening of her new custom-clothing

boutiques, Selena was in constant demand. Hispanic Business magazine

listed her as one of the most successful Latin entertainers in the

world, with annual earnings estimated at $5 million. She made her

movie debut this year, playing a mariachi singer in the Marlon

Brando/Johnny Depp feature "Don Juan DeMarco."

was there to see Jon Secada, an EMI artist who was enjoying huge success in the English

and Spanish markets simultaneously. Selena happened to be opening

the show. Brennan was suitably impressed. Selena was signed by EMI's

SBK subsidiary in December 1993. But it was another year before she

could begin work on her debut album in English. First there was the

touchy matter of selecting the right material and producers. Then

"Amor Prohibido," somewhat unexpectedly, became a huge hit in the

Latin market. Between touring with the band, filming commercials and

movie roles, and overseeing the opening of her new custom-clothing

boutiques, Selena was in constant demand. Hispanic Business magazine

listed her as one of the most successful Latin entertainers in the

world, with annual earnings estimated at $5 million. She made her

movie debut this year, playing a mariachi singer in the Marlon

Brando/Johnny Depp feature "Don Juan DeMarco."

"This is the first time I have ever made a debut album by an artist

who was too busy to record for me," Brennan groused good-naturedly

in early March. "How can you tell someone, `No, I don't want you to

play the Astrodome for 60,000 people; I want you to work on your

record?' Everyone wants her." But Brennan had little doubt that when

it did come out, the album would make Selena an international

superstar. "I think Selena can do anything she wants to do," she

said. "She can have a successful career in two languages. She's got

the pipes. She's got the heart. She's got the look. "If I had to put

my own money on the line, I would bet on this one. I would say

multi-platinum is to be expected, and the sky's the limit." Back in

1988, A.B. had invited a 17-year-old San Antonio guitarist named

Christopher Perez to join Los Dinos. Chris played with the band for

a couple of years, then quit for a year to pursue his love for rock

'n' roll. Abraham says it was only after Chris returned to the band

that he noticed the lead guitarist and the singer seemed to have

something brewing between them. Throughout her teen-age years,

Selena's career left her with little or no time for socializing.

There had been one boy, a few years earlier, who pursued an interest

in her. But Abraham hadn't allowed the two to be alone together.

Initially, he was opposed to Selena getting involved with anyone,

much less a member of the band.

"Like I said, I was a very possessive father," Abraham says. "I

thought she was too young, that her career was beginning to blossom,

and that she had a great future ahead of her. I didn't want anything

to distract her from this." But after he got to know Chris better,

Abraham came to accept the relationship wholeheartedly. "I saw how

he was, his personality, his whole being," he says. "I care for him

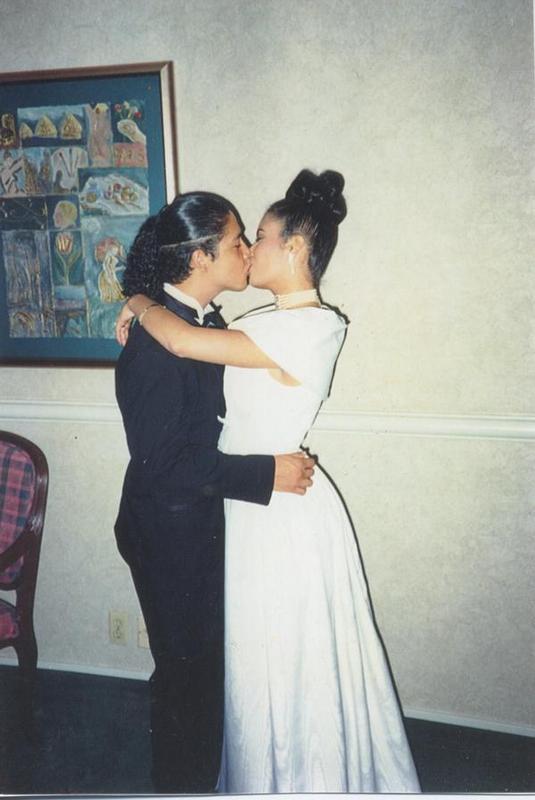

like a son now." Chris and Selena were married on April 2, 1992. The

groom was 22, the bride not quite 21. They shared a house on a

corner lot in La Molina, a working-class neighborhood on the

agricultural outskirts of Corpus Christi. Abraham and Marcela lived

next door, and A.B. lived next to them with his wife and two kids.

Among the three houses, there were nine dogs, five of which belonged

to Selena. She loved animals. While Selena felt at home in La

Molina, she and Chris were planning to move soon to more spacious

quarters. The couple had purchased land farther outside of town on

which they intended to build a house and eventually to start a

family. Selena already had picked out the furniture.

About five years ago, shortly before Selena's career went into

overdrive, Abraham began receiving calls from a San Antonio woman

named Yolanda Saldivar. The woman said she wanted to start a Selena

fan club. She told Abraham she would apply for a non-profit charter

and donate some of the money to charitable causes. At first, Abraham

ignored her. Eventually, he gave in to her persistence. "My interest

was in publicity for Selena," he says. Saldivar, who worked as a

registered nurse with tuberculosis patients at the San Antonio State

Chest Hospital, became Selena's No. 1 fan. Although she was in her

30s, she screamed like a teen-ager at Selena's concerts. She turned

her home in San Antonio into a virtual museum of Selena memorabilia,

complete with a wall-size photograph. Saldivar was allowed on the

band bus whenever Selena played San Antonio. But Selena had little

other contact with her until about nine months ago, Abraham says.

That's when Saldivar was hired, at Selena's suggestion, to manage

the Selena Etc. boutiques in Corpus and San Antonio. The boutiques

may have been Selena's way of asserting her independence from the

family. She loved to shop for clothes, and she designed the sexy

outfits she wore onstage. Now she wanted to prove that she could be

a successful businesswoman. Although Saldivar had no previous

experience at running a business, Abraham went along with Selena's

choice.

About five years ago, shortly before Selena's career went into

overdrive, Abraham began receiving calls from a San Antonio woman

named Yolanda Saldivar. The woman said she wanted to start a Selena

fan club. She told Abraham she would apply for a non-profit charter

and donate some of the money to charitable causes. At first, Abraham

ignored her. Eventually, he gave in to her persistence. "My interest

was in publicity for Selena," he says. Saldivar, who worked as a

registered nurse with tuberculosis patients at the San Antonio State

Chest Hospital, became Selena's No. 1 fan. Although she was in her

30s, she screamed like a teen-ager at Selena's concerts. She turned

her home in San Antonio into a virtual museum of Selena memorabilia,

complete with a wall-size photograph. Saldivar was allowed on the

band bus whenever Selena played San Antonio. But Selena had little

other contact with her until about nine months ago, Abraham says.

That's when Saldivar was hired, at Selena's suggestion, to manage

the Selena Etc. boutiques in Corpus and San Antonio. The boutiques

may have been Selena's way of asserting her independence from the

family. She loved to shop for clothes, and she designed the sexy

outfits she wore onstage. Now she wanted to prove that she could be

a successful businesswoman. Although Saldivar had no previous

experience at running a business, Abraham went along with Selena's

choice.

"Yolanda had been president of the fan club for four years," he

says. "I took for granted everything had been going smoothly." What

the family didn't know was that Saldivar had been accused by a San

Antonio doctor of stealing more than $9,000 in 1984 when she worked

as his bookkeeper. The Aetna insurance company paid off the doctor

and then settled out of court with Saldivar. Nor did they know that

Saldivar had failed to pay off her college loan, and had left a job

as a nurse's aide under questionable circumstances in the early

'80s. Selena misread Saldivar's obsession for friendship. When

Saldivar gave Selena a ring made of the miniature Faberge eggs

Selena loved, Abraham told his daughter he was wary of Saldivar's

motives. He wondered about the nature of her attraction. Selena

replied, "Oh, Dad, come on. Everyone's weird to you," he remembers.

Even after boutique employees complained of Saldivar's incompetent

and devious management, Selena was reluctant to believe that her

biggest fan had anything but her best interest at heart.

"Selena had the same personality as my wife," Abraham says. "If I

see one discrepancy, then I'm on the alert. But she could see 20

discrepancies and then, when they finally get ready to take action,

they say, `Well, maybe they needed the money more than I did.'"

In March, Abraham had accused Saldivar of embezzling money from the

fan club and boutiques. The family had found four checks, including

one for $3,000, she'd written to herself on the fan club account.

"If you've ever seen a cornered animal, you know how she reacted,"

he says. Abraham had no way of knowing that a few days after their

confrontation, Saldivar purchased a 38-caliber revolver in San

Antonio. "I know Selena had made the decision to let her go," says

Manolo Gonzalez. "But because of her nature, she wanted to let her

down easy. She wanted to let her go in a way that they could still

be friends. "I guess Selena saw in her a dedicated person, someone

she could trust. Selena was very trusting."

found four checks, including

one for $3,000, she'd written to herself on the fan club account.

"If you've ever seen a cornered animal, you know how she reacted,"

he says. Abraham had no way of knowing that a few days after their

confrontation, Saldivar purchased a 38-caliber revolver in San

Antonio. "I know Selena had made the decision to let her go," says

Manolo Gonzalez. "But because of her nature, she wanted to let her

down easy. She wanted to let her go in a way that they could still

be friends. "I guess Selena saw in her a dedicated person, someone

she could trust. Selena was very trusting."

In late March, Selena sent Saldivar to Monterrey, Mexico, where she

was planning to open a new boutique. Saldivar was told that when she

returned she should provide bank statements and other documents that

could establish her innocence. Coming across the border, Saldivar

called Selena to say that her car had been stolen and she'd been

abducted and raped. She sounded hysterical on the phone. Selena felt

she was stalling. But the singer still held out hope that her father

was mistaken about Saldivar. And she insisted that Saldivar see a

doctor when she got back to Corpus. On Thursday night, March 30,

Saldivar called Selena from the Days Inn on Navigation, not far from

the Q Productions office and studio. But when Chris and Selena

arrived at the motel, Saldivar failed to provide the documents

Selena was hoping for. Nor would she go to the hospital. At about

midnight, Saldivar called again to say she was bleeding internally

as a result of the rape. She asked that Selena return to the motel

alone, but Chris persuaded his wife to deal with it in the morning.

Selena left early on Friday to meet Saldivar at the Days Inn. They

went to the hospital, where Saldivar retracted her claim of rape.

There are no witnesses to exactly what happened when they returned

to the hotel. Presumably, Selena told Saldivar she was fired. A maid

cleaning a hotel room upstairs told the police she heard them

yelling. Then she heard the gunshot. She looked out the window and

saw two women running by the pool. One was screaming for help and

clutching her chest. The other woman had a gun in her right hand.

The maid says she saw her aim and fire. Selena made it to the hotel

lobby, where the clerk locked the door and called an ambulance. She

was bleeding profusely from a gunshot wound in her back. A witness

asked who shot her. "Yolanda," she said. In Selena's hand was the

friendship ring Saldivar had given her. She never got the chance to

give it back.

"The Bible says that revenge belongs to Jehovah," Abraham says.

"It's in God's hands now." As he speaks, Abraham is surrounded by a

dozen tourists and well wishers who have come to see the Corpus

Christi studio where Selena sang. Like pilgrims on a mission, they

make the rounds from the Days Inn to the boutique to the grave to

Selena's house. They sign their names on the wall and leave flowers

at the grave. Many are wearing Selena T-shirts and caps bought from

bootleggers seeking to capitalize on the tragedy. The parade of

fans, which began even before Saldivar surrendered to police after a

nine- hour stand-off outside the Days Inn, has been going on for two

weeks. Abraham, the family patriarch and spokesman, is clearly

exhausted and emotionally drained. He asks the sightseers not to

take his picture. But he cannot bring himself to turn them away. "I

know that if they came from that far off to pay their respects, then

they loved Selena, too," he says. "They are broken-hearted, as I am.

One lady told me it was just like her daughter had died. I was very

touched. That's how close people felt to Selena." The next night, on

what would have been Selena's 24th birthday, 3,000 people gather at

Johnny Canales' Johnnyland park for an Easter Mass in memory of the

gran muchacha del barrio Molina. The stage is decorated with huge

bouquets of white roses. On one side of the altar is a choir, on the

other a mariachi band.

hour stand-off outside the Days Inn, has been going on for two

weeks. Abraham, the family patriarch and spokesman, is clearly

exhausted and emotionally drained. He asks the sightseers not to

take his picture. But he cannot bring himself to turn them away. "I

know that if they came from that far off to pay their respects, then

they loved Selena, too," he says. "They are broken-hearted, as I am.

One lady told me it was just like her daughter had died. I was very

touched. That's how close people felt to Selena." The next night, on

what would have been Selena's 24th birthday, 3,000 people gather at

Johnny Canales' Johnnyland park for an Easter Mass in memory of the

gran muchacha del barrio Molina. The stage is decorated with huge

bouquets of white roses. On one side of the altar is a choir, on the

other a mariachi band.

"Is it a coincidence that we celebrate Selena's birthday on the same

day we celebrate the victory of Jesus over death?" Monsignor Michael

Heras of Our Lady of Perpetual Health Catholic Church asks in his

sermon. "I don't think so. Death was defied forever. That's what

this day is about. Forever! "The last words of Christ were, `Father,

forgive them, for they know not what they do.' That is our quote,

for it is the only way to make meaning out of senselessness." The

most touching moment of the service comes when a group of children

sets free 24 doves, one for each year of Selena's life, to celebrate

her "return to the angels." Although adults empathize with the pain

suffered by Selena's family, it was the young people who had the

most difficulty accepting her death. They identified with her --

especially young girls -- and idolized her as a role model.

In Houston, Jefferson Davis High School student Christina Galvan

delivered a speech at a campus tribute to Selena a few weeks after

her death. "Now we know how our parents felt when Ritchie Valens

died," she wrote. "Selena is our Ritchie Valens. She's our John

Lennon. She's our Elvis. We'll always miss Selena. There will never

be another queen of Tejano music." Selena would have been amazed by

the overwhelming outpouring of emotion that followed her death. Part

of the reaction was a result of the dramatic and tragic manner in

which she was killed. But Selena also touched something positive in

people, something that's increasingly hard to find in the pop music

world. She was vivacious and charming, yes, but she also believed in

treating everyone equally. She often spent hours meeting fans and

signing autographs before and after her shows. Abraham tells a story

of four women, each in their 70s, who drove down from Dallas after

the shooting. "They told me they had never seen Selena perform or

known her personally, but they had seen her on television and had

fallen in love with her. They said they could see she was a humble

person."

Carmen Read, the Quintanillas' former neighbor in Lake Jackson,

remembers the time Selena and Suzette stopped by to chat about two

years ago. "She never commented on herself; her focus was on us. It

made me feel like we were the celebrities." Until her family

attended Selena's rodeo concert at the Astrodome in February, Read

says, they really had no idea how successful she'd become. "We just

looked at the 60,000 people. I thought, `My goodness, this is our

little Selena?' We all sat there with a lump in our throats." Jose

Behar is convinced that Selena died without fully appreciating how

big she was. "She would sit in my office and I'd say, `Selena,

you're a star. You should sing or be a presenter on the Grammy's.'

She'd say, `Jose, what are you talking about? I'm not a star.' She

wasn't just fishing for compliments. That's how she was. Most

artists would be going, `How much do I get paid and where do I

sign?' "She was a humble, good-hearted person. It wasn't a facade.

It wasn't an act. She was humble 24 hours a day. She knew where she

came from. She never forgot that. Fame never came between her and

her fans."

Behar said he's come to realize that Selena's religious background

played a part in her attitude. Jehovah's Witnesses don't make a big

deal out of holidays or birthdays, and they don't believe in any

form of idolatry. Selena loved to sing and entertain; the star part

didn't mean much to her. Manolo Gonzalez thinks it was Selena's

sense of common decency that led to her death. "She went to fire

(Saldivar) personally," he says. "Nobody does that in this business.

I mean, this is an artist generating several million dollars a year,

and she would go to the mall by herself. Her dad kept telling her to

be careful. She said, `Dad, people aren't that bad.' " Saldivar has

been charged with murder. Her trial is set to begin Oct. 9. Abraham

says that he wishes he'd fired Saldivar sooner. But he

adds that no

one ever imagined she'd be capable of violence. He blames himself

for putting Selena in a position where she could become a victim by

pushing her into a musical career in the first place. "I think,

`What if I hadn't done that? What if we hadn't left the spiritual

things aside?' She would have been a dedicated servant of God." The

tragedy has brought the family closer together and led them to

rededicate themselves to their religious beliefs, Abraham says.

adds that no

one ever imagined she'd be capable of violence. He blames himself

for putting Selena in a position where she could become a victim by

pushing her into a musical career in the first place. "I think,

`What if I hadn't done that? What if we hadn't left the spiritual

things aside?' She would have been a dedicated servant of God." The

tragedy has brought the family closer together and led them to

rededicate themselves to their religious beliefs, Abraham says.

"We take life for granted, you know. In our daily hustle to make a

living, we forget our spiritual needs. I have no doubt that we'll

see Selena again, when she comes with the resurrection." Meanwhile,

he's still got a career to manage. It is a sad irony that Selena's

death has focused more national media attention on Tejano music than

it's ever received. "From this horrible, tragic death, there will be

some who come to know and hear of this music called Tejano," says

Rudy Trevino, the producer of the Tejano Music Awards. "Selena, of

course, was the single most important Tejano artist, even before her

death. She opened more doors than anyone." Behar expects the

explosion of awareness that followed Selena's death to have

long-term implications in the music business. Stores that have never

carried Latin music before are now stocking Selena's albums. Other

Tejano artists may follow. "Selena will be a superstar," Behar says.

"The last chapter of this story has not been written yet." While

Selena was proud of her Hispanic culture and heritage, she was

elated at the possibility of appealing to a wider audience by

singing in English. She had completed five tracks for her new album

at the time of her death.

The album signaled a new sound for Selena. She was being packaged as

a pop diva, comparable to Janet Jackson or Mariah Carey, but with a

Latin touch. "I Could Fall in Love" is projected as the first single

from the new album, due in July. The posthumous release also will

include A.B.'s remixes of "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom," "Como La Flor,"

"Techno Cumbia" and "Amor Prohibido," as well as two previously

unreleased tracks featuring Selena singing with a Mexican mariachi

band. EMI is negotiating for the rights to a duet Selena recorded

with David Byrne that was left off the soundtrack to "Don Juan

DeMarco." "That was her biggest dream, of crossing over," Abraham

says. "Because she was born here. She was an American." But for him,

Selena the superstar will never be more real than the image of the

nervous little girl making her debut at his restaurant in Lake

Jackson. He treasures his memories. "Every time I would see her, the

first thing she would do is come hug and kiss me," he says, his eyes

misting over. "I go home and I take the videos and tapes. Sometimes

she makes me laugh. The others, my kids and wife and Chris, it's too

painful for them. They see the videos and start crying. To me, it's

soothing. "It's like she's on vacation. She's still alive; she's

just not here."